How to use questioning effectively and let your pupils be heard

How many questions do you think you ask a day? Who should be asking the questions in your classroom to progress pupil learning? It might not be who you think…

Research has shown that teachers are asking as many as two questions every minute, every day. In a surprising, stark comparison, children are reportedly asking just five questions per hour! That roughly equates to 600 teacher questions per day compared to just 25 by children!(1)

Furthermore, with pressures to deliver progress in every lesson, teachers are limiting the ‘wait time’ pupils are given to respond to their rapid-fire questioning. It is estimated that teachers often wait less than a second before throwing the question to another pupil or answering it themselves(2). Academics recommend that pupils are given around three seconds thinking time for a lower-order, factual recall question and up to ten seconds for a more substantial, higher-order question(3). In classroom practice, this may seem a painful period of silent time waiting for the brain wheel-cogs to turn but, in fact, allows the children space for deeper thought and idea connection, whilst also allowing them practice of thoughtfully constructing responses.

Questioning is a valuable tool in assessment for learning but how can we balance our professional practice to meet the curriculum objectives and nurture children’s inherent inquisitive nature and let their voices be heard?

Effective questioning

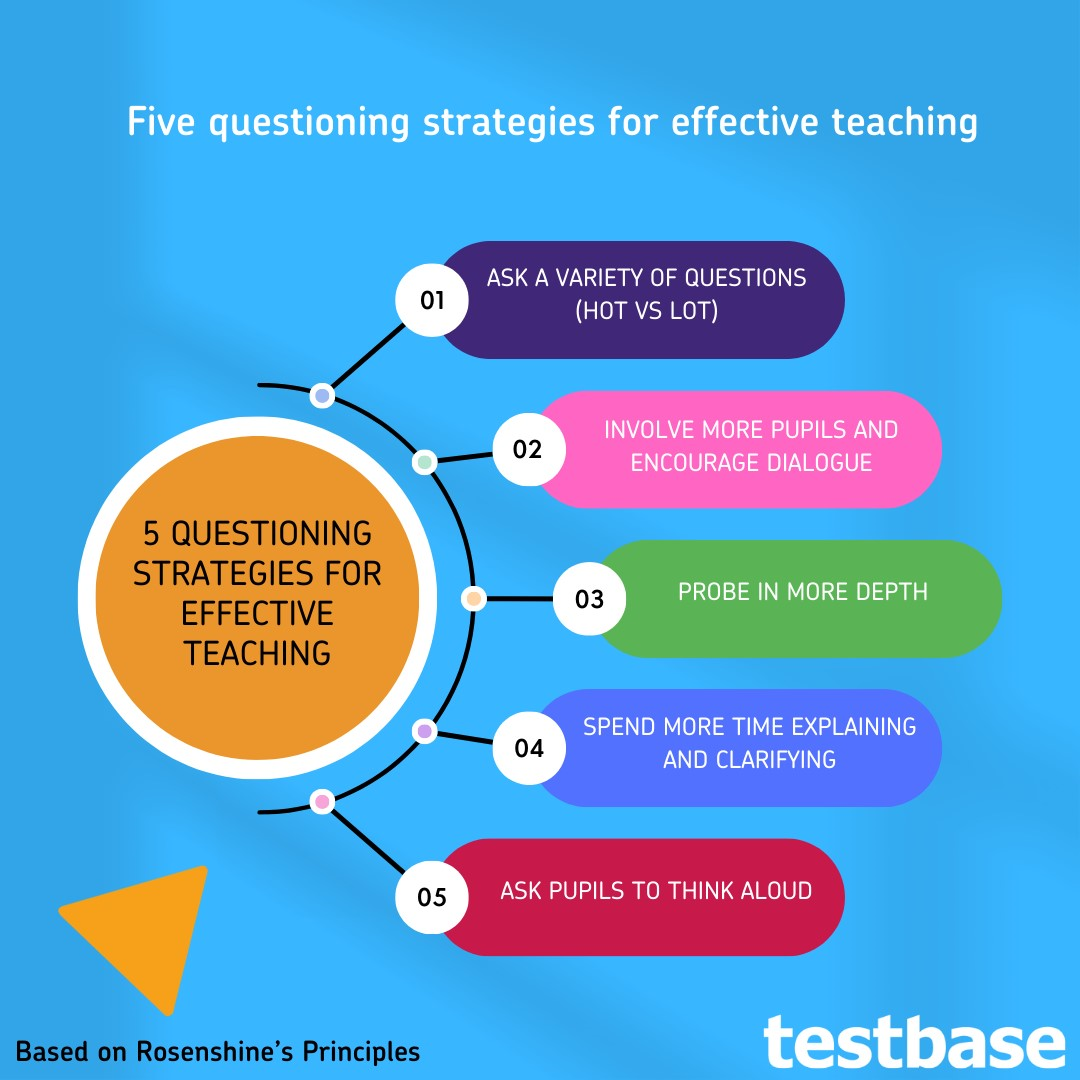

The answer doesn’t need to mean vast changes to your practice. A few effective changes to how and when you pose questions can make all the difference. It has been shown that teachers are relying on the use of closed questions in order to deliver a pacey lesson(4) and to achieve the lesson’s learning objective. These are great for a quick assessment of knowledge or fact recall but tend to deliver only short responses and lower-order thinking with little engagement with the learning. Research has shown that these types of questions are not only unchallenging but also limit opportunities for creative and enriched thinking(5). Open questions, on the other hand, encourage divergent responses, promote dialogue and can nurture meaning-making application of new concepts to new situations(6). Embedding this as a standard practice in your classroom allows your pupils the opportunity to express their thoughts, make curriculum connections and promotes a more profound level of learning. Rosenshine writes that ‘more effective teachers’ employed the questioning strategies shown in the infographic above (based on Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction, 2012) to encourage children to have more time thinking and speaking and the teacher to spend more time listening and assessing levels of progression.

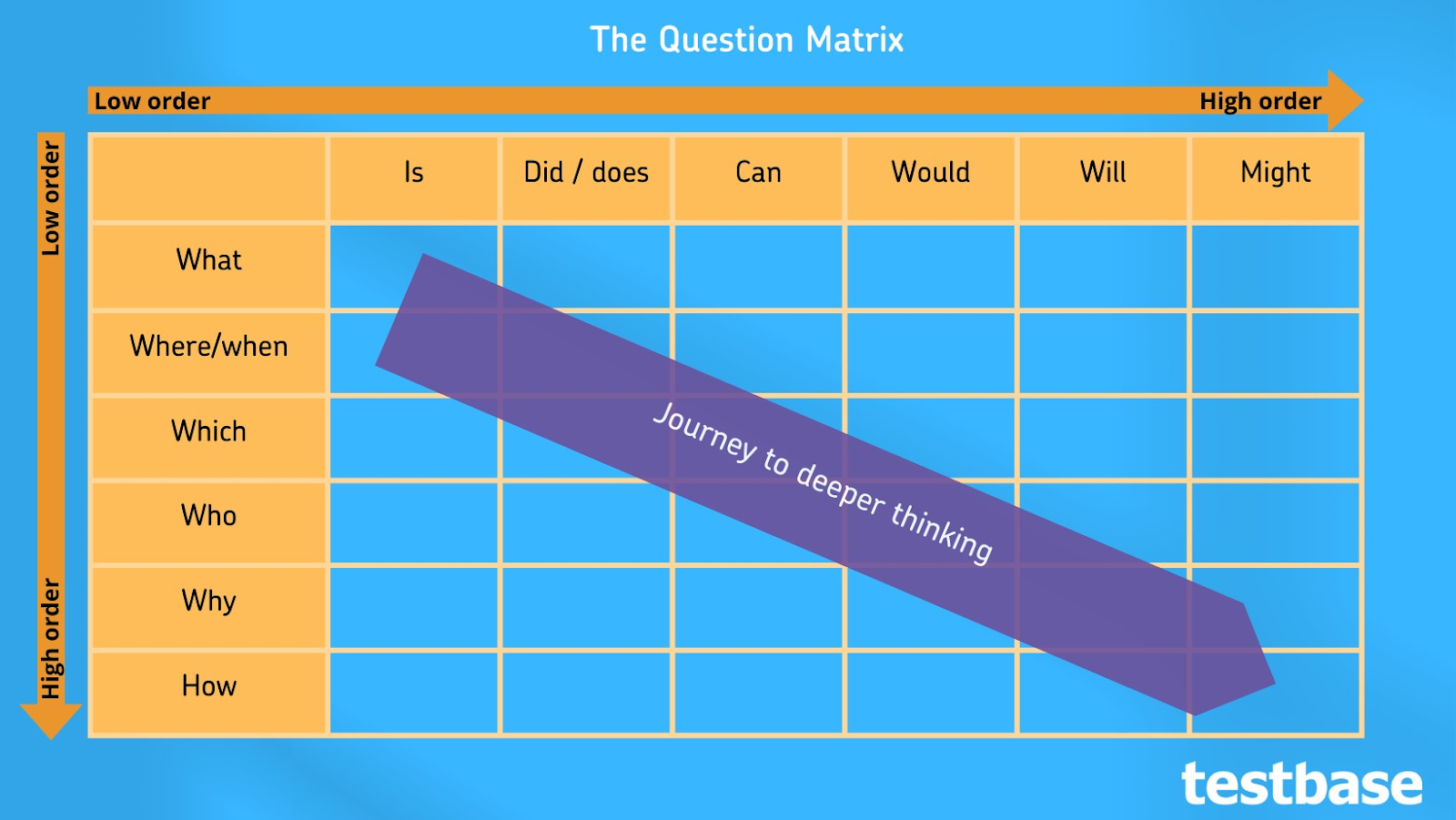

Moving from low to higher-order thinking

The Question Matrix relates to Bloom’s Taxonomy and is a useful visual for promoting and reflecting on your questioning practice to ensure you ask a range of low and high order questions – both have their place in securing different types of learning. The top left question stems are the basic retrieval, fact-finding questions, typical of lower-order thinking. These have their place in the classroom (maths fluency, checking knowledge recall, reading retrieval) and shouldn’t be eliminated completely but need to be supplemented and balanced with more thought-probing questions. As you move through the grid, you increase the level of questioning – allowing pupils to hypothesis, make connections and explore their learning. A simple reframing or a question can make all the difference to extending learning opportunities and deepening understanding.

References

- Carr, D., 2002. The art of asking questions in the teaching of science. In: S. Amos and R. Boohan, eds. Aspects of teaching secondary science. London: Routledge Falmer, 15–20.

- Hastings, S., 2003. Questioning. Times Educational Supplement. Available from: https://www.tes.com/news/questioning [ 4 Jul Accessed 1 Sep 2018].

- Rowe, M.B., 1974.Wait-time and rewards as instructional variables: their influence on language, logic, and fate control. Presented at the National Association for Research in Science Teaching, April 1972 Chicago, Illinois.

- Albergaria-Almeida, P., 2010. Classroom questioning: teachers’ perceptions and practices. Procedia- social and behavioural sciences, 2 (2), 305–309.

- Harlen, W., 1999. Effective teaching of science. a review of research. Edinburgh: Scottish Council for Research in Education.

- Smith, P.M. and Hackling, M.W., 2016. Supporting teachers to develop substantive discourse in primary science classrooms. Australian journal of teacher education, 41 (4), 151–173

Follow our social media channels for more education news, CPD and support on getting the most from your Testbase subscription: